Trending

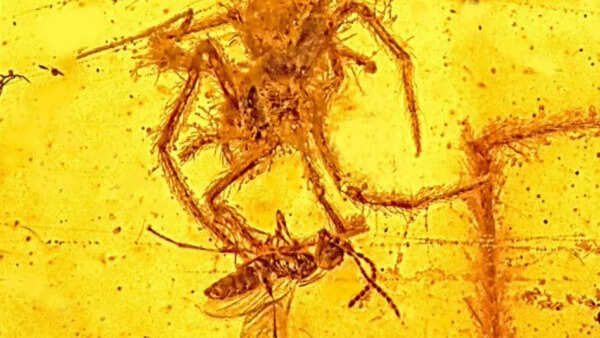

Wasp from the dinosaur era found preserved in amber—its jaws are unlike anything seen before

A unique parasitic wasp from 99 million years ago, preserved in Cretaceous period amber, featured a Venus flytrap-like structure on its abdomen. This structure likely allowed the wasp, named Sirenobethylus charybdis, to trap insects to shelter its larvae, showcasing a previously unseen evolutionary trait among insects.

A newly identified parasitic wasp that lived 99 million years ago had an evolutionary trick unlike anything seen in modern insects. Preserved in amber from the Cretaceous period, the wasp—now named Sirenobethylus charybdis—had a Venus flytrap-like structure on its abdomen, which scientists believe may have allowed it to trap other insects and use them to shelter its young.

The discovery, published in BMC Biology, came from a study of 16 wasp specimens encased in amber found in Myanmar. I was found in the Kachin region near the border with China and was purchased by a fossil enthusiast several years ago before being donated to Capital Normal University’s Key Laboratory of Insect Evolution and Environmental Changes in 2016.

“When I looked at the first specimen, I noticed this expansion at the tip of the abdomen, and I thought this must be an air bubble. It’s quite often you see air bubbles around specimens in amber,” said study coauthor Lars Vilhelmsen, a wasp expert and curator at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

“But then I looked at a few more specimens and then went back to the first one. This was actually part of the animal.”

Credit: X/@qikipedia

The structure was clearly movable, as it appeared in different positions across various specimens. “Sometimes the lower flap, as we call it, is open, and sometimes it’s closed,” Vilhelmsen explained. “It was clearly a movable structure and something that was used to grasp something.”

Since no modern insects have anything quite like it, researchers had to look outside the animal kingdom for a comparison. They eventually linked it to the Venus flytrap, a carnivorous plant that snaps shut on prey.

However, here’s the catch: the researchers theorized that the wasp used this strange abdominal trap not to kill, but to hold onto a host long enough to inject its eggs. Once released, the unfortunate creature would become an unwitting host for the developing larvae, which would eventually consume it.

“There’s no way you can know how an insect that died 100 million years ago was living. So you look for analogs in modern insect fauna. Do we have anything among wasps or other groups that looks like this?” Vilhelmsen said.

“And there’s no real analog within insects. We had to go all the way out of the animal kingdom into the plant kingdom to find something that remotely resembled this.”

While some modern parasitoid wasps exhibit similar behaviors—like cuckoo wasps, which lay their eggs in other wasps’ nests—the flytrap-like structure of Sirenobethylus charybdis makes it unique.“This is something unique, something I never expected to see, and something I couldn’t even imagine would be found,” Vilhelmsen said. “It’s a 10 out of 10.”

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Visual Stories

Tired of too many ads?go ad free now